Optimism

Why We Can’t Stop Watching the News

The optimism bias and the human urge to seek information.

Posted April 30, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

In the recent months, amid the biological and psychological upheavals of the pandemic, human beings around the world have been caught in another kind of an avalanche—information overload. Suddenly, many of us are unable to unglue our eyes from our screens. We are following the new developments, reading the new theories, listening to the new interpretations, debating the new reports. We do it in different languages, across different time zones, and all while complaining that our avid consumption of the news is making us miserable.

What mechanisms are behind this insatiable thirst for information?

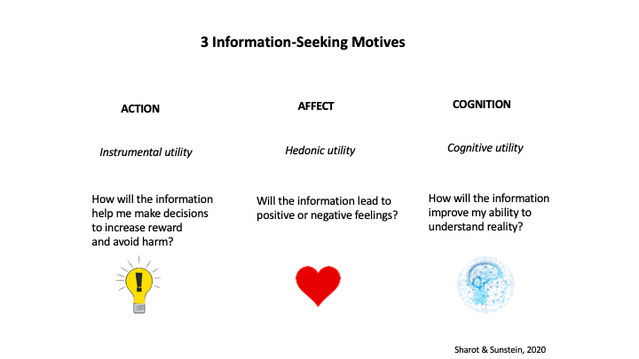

According to neuroscientist Tali Sharot, we seek information because of what we predict the information will do to us, rather than what it actually does. And it all has to do with three motives that drive our quest for knowledge: utility, cognition, and emotion.

Here is Dr. Sharot in her own words on the human fascination with knowledge.

Why do human beings have the urge to seek information?

Our research has shown that there are three different motives for why humans seek information. One is instrumental utility—can the information help me? With the pandemic, you might be thinking, “If I get more information, I can plan better or protect myself better.”

The second motive is cognitive utility—can I use the information to understand the world better? In our current circumstances, cognitive utility is probably one of the main functions of information. There is a lot of uncertainty, and we are trying to reduce it by seeking more information. Although, I think that the information we are getting currently might lead us to experience even more confusion and uncertainty. For example, the conflicting accounts we hear about acquiring immunity against the virus. So, more information might be negatively affecting our cognition.

The third motive is affect—can the information make me feel certain emotions? For example, you might keep watching the news with hopes of hearing something good, like a new vaccine or progress with our fight with the virus. Even if we keep being disappointed, we continue to seek information, because we feel like we will finally receive some good news. That’s where the optimism bias comes in.

What are the brain mechanisms driving all this information-seeking?

There is evidence that the reward system and dopamine are involved in knowledge-seeking. But exactly how that works still remains unclear. Earlier hypotheses stated that information is a higher-order reward in and of itself, because knowledge is always valuable. According to these theories, any kind of information—positive, negative, or neutral—will be coded in your brain as a reward, causing it to release dopamine, and drive you to seek more information. What we have found is that when it comes to midbrain dopamine systems, only positive knowledge is coded as a higher-order reward. So, when these brain systems code the value of the information based on these three motives, on average, the value of the reward will be higher when it is positive.

Is knowing always better than not knowing?

In economics and early neuroscience research it has been a classical assumption that knowing is always better than not knowing. But I don’t think that’s true. All three motives could be negative—you could expect the information to be bad, not be useful, and have a negative effect on your actions. Then the value of the information will be negative and therefore you would avoid information. The fact that people avoid information gives us a big clue that more information is not always positive for the brain. If you expect the information gain to be negative, then the brain will not react to it like it does to a reward. That will cause inhibition and lead you not to approach information, but rather to avoid it.

Can the way we seek information be a window into our mental health?

Our recent research shows that people are more likely to seek information when they find it useful, or positive, or when it’s about things that they often think about. On an individual level, people can be characterized into groups based on the motive that best explains why they are seeking information. Some people are dominated by affect, others by action, others by cognition. It turns out that these three groups differ in mental health outcomes. People most resilient to psychopathology are those who seek information mostly because of cognition. In other words, their information-seeking is largely driven by their desire to understand the world around them. On average, your group will stay stable over time. But people change and states matter. If I put you under certain conditions, or if I change your affective state, it can change your information-seeking motive.

The question is whether information-seeking is causing psychopathology or whether psychopathology is causing information-seeking. Our hypothesis is that it’s bi-directional. The way you seek information is probably going to make some mental health conditions worse or perhaps even protect you from certain conditions. But also, if you already have certain conditions, it can drive your information-seeking patterns. At this point, it’s all correlational, however, and we don’t know yet about causation.

Why do many of us have a tendency towards an optimism bias?

The optimism bias is about our expectations of the future—when we expect things to be better than they actually are. Research has shown that the optimism bias enhances motivation, protects our mental and physical health. A study published in Nature a few years ago showed that a society will develop to be optimistic rather than pessimistic as long as you are not in a threatening environment. Having this bias means that people not only expect positive things, but they think they can do things to protect themselves. With the current circumstances, for example, people might think that they are less likely to be infected with the coronavirus because they think they have control over it. To some extent they do—when we stay home, we protect ourselves.

The optimism bias can also enhance motivation. If you think you can do well, you will likely put more effort into what you are doing. What we found in our research is that if you put people under threat and enhance cortisol, there is a quick change in how people learn to update from positive and negative information, which results in the optimism bias going away. What is adaptive about the optimism bias is that it is flexible, and that it adapts to the environment.

How can we stay optimistic during difficult times?

I think anticipation and agency are key to preserving our well-being. It’s important to have something you can look forward to, especially now that a lot is being cancelled. Secondly, try to regain a sense of agency or control over your circumstances. You could do that by starting new projects, or even deciding to consume less news. In a recent study we found that people who had more agency were more optimistic. Moreover, agency and optimism were also protective factors—people with a high sense of agency felt less reduction in their happiness at the moment. As a journalist once told me, happiness is being in the waiting room for happiness, so don’t underestimate the power of your expectations on your well-being.

Many thanks to Tali Sharot for her time and insights. Dr. Sharot is the director of the Affective Brain Labat University College London. She is a Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the department of Experimental Psychology at UCL and a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow. She is the author of several books, including The Optimism Bias: Why We're Wired to Look On The Bright Side.

References

Sharot, T., & Sunstein, C. R. (2020). How people decide what they want to know. Nature Human Behaviour, 1-6.